Check out my review plus my time at the Public Enemies press conference with Marion Cotillard, Michael Mann and Johnny Depp.

Check out my review plus my time at the Public Enemies press conference with Marion Cotillard, Michael Mann and Johnny Depp.HOME

"I'm the Dude. So that's what you call me. You know, that or, uh, His Dudeness, or uh, Duder, or El Duderino if you're not into the whole brevity thing."

Check out my review plus my time at the Public Enemies press conference with Marion Cotillard, Michael Mann and Johnny Depp.

Check out my review plus my time at the Public Enemies press conference with Marion Cotillard, Michael Mann and Johnny Depp. Director: Michael Mann

Director: Michael Mann

Public Enemies features a theme seen in most of your work, that clash of law versus lawlessness. Why are you exploring this, and why choose the life of John Dillinger?

I became fascinated with Dillinger, because of certain mysteries in his life. First of all, he was very bright, and great at doing what he did. And he's regarded as one of the best bank robbers of American history, to whatever extent that's worth. He was very very current, very contemporary. Very sophisticated. He planned his robberies with great precision and forethought, and employed techniques picked up from the military by a guy called Herbert K. Lam - where the expression 'on the lam' came from. He mentored Walter Dietrich, Walter Dietrich - the guy who died at the beginning of the film - mentored John Dillinger. So Dillinger's time in prison is really a post-graduate course in robbing banks. But what really interested me, is he not so much gets out of prison - he explodes onto the landscape, he is determined to have everything right now. And lives the dynamics of maybe four or five lifetimes in one, and that one life is only thirteen months long and it has the intensity and white hot brilliance to it, and an indefatigable brio, that I found stunning in view of the fact that he had no concept of future. That he could plan bank robbery with great precision, but they couldn't plan next Thursday.

There was no sense of, as there was with Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and the Hole in the Wall gang, of making a quarter of a million dollars, then go to Brazil for a year and a half, and chill out. There was no endgame. There was this very very intense live for today, and whatever happens tomorrow, it's fated. It's not that by decision making or consciousness it's determined, it's just fated. And it's part of current thinking in the '30s - it's within three years of Hemingway writing Death in the Afternoon, about facing death straight on if you're a matador... Writing that every story ends the same way, with death. And not something that you'll transcend, or go to heaven, or any other fiction - but not something that's depressing, it's just fact. We have Red [John 'Red' Hamilton, Jason Clarke in the film] saying, 'when your time's up, your time's up'... and people had expressions like 'there's a bullet with your name on it'.

The spirit of this guy - for example, even when everybody's dead and gone... and he has the outrageous audacity to walk through that police station. Which didn't happen the day of the Biograph, it actually happened three days before. Well, it was just stunning, so for me to explore it and to try to bring the audience into some real intimate relationship with it, became the challenge of this work. To as much as possible to locate the audience in his shoes, in his skin, looking through his eyes. Y'know - what's he thinking? What's he thinking in the Biograph, when [in Manhattan Melodrama] Myrna Loy - who looked like Billie Frechette - says 'Bye, Blackie', and he's watching Blackie, who's played by Clark Gable - who's derived from Dillinger! So it's Dillinger watching Gable being Dillinger! And Gable seems to be thinking more about the future and how should I look at mortality than Dillinger is. And how did those words fall upon him? He doesn't know that there's 30 FBI agents outside, who are planning to kill him. So that was the real engagement.

Reportedly, Christian Bale was your first choice for Melvin Purvis, what was it about him that made you see him in the role? It says in the production notes that, in between takes, he kept up the Southern accent - is that something you encouraged, or was that his choice?

That's how Christian does it. Every actor's different. Some actors will put on that - being completely in character when they show up for work. A brilliant actor - Stephen Graham, he picked up that Chicago accent [clicks fingers] in two days. And that was just amazing, and then the second I said 'cut', he's back to, you know [Graham is from Kirkby, Merseyside], and I could barely understand him - I need subtitles! Christian, on the other hand, just dives into the deep end of this swimming pool and he's there the whole time.

The character of Melvin Purvis, if you know American culture and patterns of immigration and ethnicity - he was a member of the landed gentry. They were people who settled in the United States in the 1600s, they were from the richer southern counties of England, and they got the best land - Virginia and South Carolina. For example, the people who settled in Appalachia, where [The Last of the Mohicans protagonist] Hawkeye's ancestors would have come from, were the people from the borderlands who got kicked off the land after the union of England and Scotland. And they got what was left over, which was this brilliant piece of real estate, the only thing is, there's a bunch of hostile American Indians who said 'this is our land', so it was dangerous. So that was the tenement slum of the 18th century.

So he emerged as a very rigid young man, with very specific treasured traits, a very specific code. One of which was - in addition to chivalry, not saying no, and loyalty - was conflict resolution through violence is totally acceptable. A kind of a duelling ethic. But he breaches those codes when he drinks J. Edgar Hoover's kool aid, when he embraces the notions of expediency. Which means setting aside habeas corpus, persecuting the innocent, using torture and those kind of things.

So I had to have somebody who could embrace those original values. And Christian, clearly, was the guy for me. When he got the accent down, he would [adopting Southern drawl] talk like this, in this genteel Southern accent, and it made his three year old daughter nuts! She'd say 'daddy, stop talking like that!', and he'd say 'Well, dear, I have to play Melvin Purvis, and I will be doing so for the next...' [drowned out by laughter, laughs] And that was it! He was a dream, though, a dream to work with. He's a great guy, and a great actor.

Is there a sense that, as Dillinger is such an American folk hero, that the film can't help but glamorise him?

Who glamorised him?

Just the film itself, you can't help but sympathise with him...

The media glamorised him?

Yes, in a...

Well, the media didn't glamorise him. Contemporary news reports at the time glamorised him - there was something from the Daily News, a reporter who interviewed him at Crown Point, who wrote this big piece about how genteel he was, how charismatic, how well-spoken. How he didn't conform at all to the stereotype - or archetype that they had in their minds of the criminal class, who they thought was some slothful somebody with dark skin and a low forehead and eyebrows. That was the take. And he would basically be this middle class guy, who was charming, who would be able to make you feel he was your best friend in three minutes.

And with Dillinger, this was absolutely tactical. And when they got this great press, which they did all the time, their heads didn't get large. They planned their robberies with sobriety with great discipline, they had great operational security. And he was popular for [hitting arm of chair for emphasis] a very very good reason. There'd been forty bank failures in this recession in the United States - and the enmity towards the banks is palpable in the United States. And Chicago alone, in 1933, of 166 regional banks - meaning outside the Loop - 140 had failed. Employment wasn't 8%, it was 25%. One out of four were hungry and cold and miserable. And most people blamed the banks.

So Dillinger is stealing from the banks, and he's sharp enough to make sure that he treats female hostages well - because he knows that they're all going to be interviewed. When Saager, the car mechanic who was taken hostage [as Dillinger escaped Crown Point prison] was released, there was a MovieTone newsreel - that's where we got that scene from, it's just a verbatim copy, it's a xerox of the mechanic trying to sing out of tune on MovieTone news. So the attitude in the country, which was very wired. Everybody had only one medium - radio. And everybody listened to it, and the biggest radio commentator in America was Will Rogers, and the way Will Rogers reported what happened at Little Bohemia was like this - he was a very folksie guy - 'well, the FBI had the whole place surrounded, and Dillinger was inside, and some other guys came out, some civilian conservation corps workers, so they just shot them instead. Dillinger and his whole gang got away. They probably will get Dillinger some day, when they shoot down a bunch of innocent bystanders, and they get Dillinger by accident'. That was kind of the media take, there was a begrudging admiration and ridicule heaped on the authorities.

As a person who grew up in Chicago, what part did the story and films inspired by it have in your upbringing and childhood? And, did they influence your filmmaking at all?

Chicago, as a city, it's a very tough-minded, and ironic, and humorous kind of city. It really has a Brechtian kind of wit to it. Which it why Brecht set [The Resistable Rise of] Arturo Ui in Chicago, and movies like The Front Page and His Girl Friday all come from Chicago writers, and are all about the newspaper business in Chicago. You know, hiding a wanted criminal in a roll-top desk - that's very Chicago. I remember driving down Lincoln Avenue with my dad when I was about seven or eight or something, and he said 'oh, there's the Biograph, that's where they killed John Dillinger'. 'Well, who's John Dillinger?' It's all kind of folklore that's embedded in the brown bricks of the city. So it's my neighbourhood physically as well as culturally. My wife and I used to go to the Biograph, because it was an arthouse by the time the early '70s rolled around. So, it's plays a big part.

And, becoming a filmmaker, did watching these gangster movies as a kid, did that inspire you?

Not at all! First of all, I loved the literature of the period: Hemingway, Faulkner, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and particularly someone who's not as well read now, [John] Dos Passos and the USA Trilogy - Big Money particularly, about the Depression. And the '30s is a fascination for me photographically, because of Roosevelt and the WPA [Works Progress Administration], and Dorothea Lange's photography. And the first recordings of folk music, and prison chain-gang music, and blues - we used some of it in the film too, Blind Willie Johnson and the spiritual that's there in the beginning. And it seemed like the rest of the 20th century was given birth in the '30s, not the '20s.

The world becomes streamlined, not just in the shapes that changed from neo-classical, square stuff. But in systems, all systems, centralisation. The commercial airplane is four years old. And Hoover innovatively takes that over, sends agents everywhere - networking, triangulation, none of this stuff had happened. America was very much, outside of the big cities, was absolutely in the middle of the 19th century. If you committed in a robbery in Wisconsin, and crossed the border into Illinois, you were home free. And there was nobody with a badge or any authority to go after you. It was almost like primitive territories. The use of data collecting, and disseminating information, it was all brand new. The highways were brand new - they had been built in the 1920s, they were only four or five years old... So these guys, armed with modern weapons, being innovative, using cars, travelling the highway system, going anywhere they wanted, were just about invincible.

So, that part of it. But it's really the magic of trying to be intimate to Dillinger, trying to live in the '30s, to place the audience - as much as I'm able to do that - in 1933, rather than look at 1933, and be inside the frame of reference of Dillinger with his period psychology. And that was the real traction for me. One other thing, the movies of the '30s that I relate to aren't those movies. It's more Zero de Conduite [Jean Vigo film], and some French movies, than it is those pictures. Or if I went to those pictures, it would be to see [actor, star of original Scarface] Paul Muni do acting that's directly from Stanislavsky, not filtered through the Actors Studio, so I wasn't really a huge fan of the gangster pictures from the period.

How easy was it for you to get access to the locations you wanted in Chicago? And, how difficult was it to dress them up to fit the period?

It was very difficult. Well, there were obvious things, where you'd have a building from the 1920s, and then you'd have three others that weren't. And when we did the Biograph... they took down the authentic marquee about a year before we got there, which was a great tragedy. So we had to put that back. And then we had to change the ground level of all those buildings and put facades on all the buildings, and put cobblestones down, and put trolley tracks in the middle.

But there exists in the south-western quarter of Wisconsin a very unusual area. Wisconsin had a boom economy at the turn of the century, from around the 1860s, after the Civil war, all the way to about 1910 - it was lumbering, and iron ore. And so it was fabulously wealthy, so leading families in town, like Black Falls, Wisconsin, always went to Europe in the summer. It was like Silicon Valley in the '90s.

But when lumbering was over, the south west quarter of Wisconsin doesn't have rich agricultural land like the rest of the state did. So their economy just trickled along. Consequently, there were these fabulous towns and small cities that were built up, they were very well maintained, but they never got their Walmarts, or their Burger Kings, or their McDonalds. So the silhouette of these towns is perfect - exactly the way they would have been in the '30s. They've got this beautiful county court house, county square, and at the end of the main street, the forests and the hills begin. So we did a lot of shooting up there, and also in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. The small town, where they escape the Crown Point jail, that whole town is a town called Columbus, Wisconsin - it's gorgeous - but we still had to change the ground for it.

The film has been praised for its fidelity to the truth, but how important is that for you? And when do you decide to take dramatic licence?

I hope I don't have a slavish adherence to actuality. It's only when it's magical, or when it means something, do you go there. So the magic of being able to shoot in the real Little Bohemia, in Manitowish, Wisconsin, for example, was superb. For Johnny Depp to be in the same bed John Dillinger really was in, for him to be shocked awake by gunfire, and see the ceiling that Dillinger saw, and to look out the window to see where this attack was coming from, was phenomenal. Same too with the Crown Point jail, it had been abandoned in '74, was falling in on itself.

There's some stuff on the Internet now, that has some footage of what that looked like when we first went there. We restored it, because you couldn't invent a place that was like that. He didn't take six or seven people hostage, he took seventeen guards hostage with that little wooden gun he'd carved. It wouldn't have been credible if we'd put that in the movie, so we had to tune it down. The Biograph, for him to die on the same piece of real estate that the real Dillinger did. I'm most interested in how you think and how you feel if you're an actor. So if it's those things that provoke that belief, or the suspension of disbelief in the moment for the actor. And so too with the text.

The periodicity of the courtroom, just to take a lighter scene, the feeling of zeal in Purvis. I think that audiences are quite brilliant perceptually, we're smarter than we even know. And we spot things that are wrong, we feel wrongly about them, and sometimes the intellectual conclusion doesn't even land. We perceive the patterns, and things in the far distance, we recognise truth-telling style in the visual, even though we don't know it.

Where licence comes in, like I said, he didn't go into the Detective Bureau the day of the Biograph, he went into it three days ahead. Baby Face Nelson didn't die at Little Bohemia, he died exactly that way, with exactly those people in exactly the same shootout, but it happened about a month later I believe. Or I might conflate characters, Makley is really two characters who did the same job, Charles Makley and Russell Clarke. The key thing for me is authenticity - how they thought, why they thought the way they did. And with that, we do a lot of work with period psychology. How to come onto a woman. How did Dillinger know how to come onto a woman? We imagine he went to movies to try and find out.

I was going to do them in order with Michael Mann after Marion Cotillard's press conference, but then I thought I would do the actors first and the director last.

I was going to do them in order with Michael Mann after Marion Cotillard's press conference, but then I thought I would do the actors first and the director last.John Dillinger is an absolutely bona fide folk hero, but what was the draw of playing this outlaw whose name is virtually synonymous with the gun-slinging American past?

Well, first and foremost, when I was like 9 or 10 years old, I had a fascination with John Dillinger, I don't know why - and probably not a healthy one. I think it was something about the twinkle in his eye; there was something mischievous that intrigued me. But, in terms of taking on the role, the idea that the guy was called Public Enemy Number 1, but, if you really think about it, was never an enemy of the public. That I found intriguing and challenging.

What is it about this character of John Dillinger that you think fascinated the public? And, famously, he died after watching Manhattan Melodrama, what would be the film you'd like to watch before you died?

[Laughs] If I had to see a last-ever film, it would be Withnail & I. Without a doubt, no question Withnail and I!

I think, especially with a guy like John Dillinger, if you think about where we were in 1933 - well, it's not unlike where we are now. The banks were sort of the enemies, and it was taking the knees out from under everyone. Displacement was a kind way of putting it - their lives were being ripped from them. And there's JD, who arrives as one of those people who've been ten years in prison for some youthful, ignorant, drunken crime. Ten years, and he arrives on the scene in the ultimate existential arena, and says 'I'm gonna stand up against these people'. So I think, for me, what's fascinating is the guy who says 'I'm not gonna take it'.

[In reference to a short scene where JD sings the country standard The Last Roundup, after a jail break] First Sweeney Todd, and now this, it was almost as if you were looking to crowbar in some singing...

I almost broke into dance... I just might now!

Why not? Just wondering if you've been bitten by the singing bug?

I've only been bitten once, and it was an indirect bite. No, no, no. I sang the one time on Sweeney because, well, basically I had no choice.

But you sang well in this. I know it was only a few lines....

Oh, yeah! I do sing in the film - is it in? I haven't seen it!

Any recording contracts come your way yet?

You know, some people better stay in their own little arena. [laughs]

How did you research for the role? Did you watch previous films about him?

I certainly had a strong memory of Warren Oates' John Dillinger in the John Milius film [Dillinger, 1973]. But, I hadn't seen it in years. I do remember there was a certain palate that was limited. And I thought there were more colours to be offered - without being too esoteric about it. If you think about the information that has come out since - some of Dillinger's own words have surfaced. So there's a bit more to the story, a little more dimension. And that was what I was hoping for, to add some of that.

Stephen Graham [Baby Face Nelson in Public Enemies] over here is our rising star - how did you two get on?

We hated each other, and we fought constantly. [assembled journos laugh] I think he's magnificent, one of my favourite actors of all time. What he did in This is... [journos, in unison, 'England!'] England... absolutely destroyed me. What he did, and what Tomo did in that film of Shane Meadows', took me to my knees. He's someone I'm going to fight to get... I'm going to force him to be in every film I do - even at gunpoint!

You've mentioned you've not seen the film, and did a double-take at the poster as you came in - do you not like looking at yourself? And what's it like now that you're a big star?

If I can avoid the mirror when I brush my teeth in the morning, I will. I find security and safety in the most profound degree of ignorance. If you can just stay ignorant, almost everything will be ok. Just keep walking forward, and it's ok to notice things, and look at things, but, to judge things will bog you down. So I don't like watching myself in the movie, because I don't like to be aware of the product, I like the process. I enjoy that. That [pointing at the oversized poster] is... not my fault. I didn't do it!

In terms of your success, can you get your head around it? Did you think your time had come?

I went through 20 years of basically what the industry defined as failures. So for basically 20 years I was defined as box office poison. And I didn't change anything in terms of my process. That little film Pirates Of The Caribbean came around, and I thought yeah, that would be fun to play a pirate for my kiddies, and all that stuff. And I created the character in the same way I created all the other characters, and... nearly got fired. And thank god they didn't, because it changed my life. I'm hyper, super-thankful that radical turn happened, but it's not like I went out of my way to make it happen.

You've played a lot of real-life figures in Blow, and Donnie Brasco, and now in Public Enemies, what attracts you to that? And, who do you want to play next?

Yeah... who would I like to play next. I don't know, Carol Channing, maybe. I do like Carol Channing, very much! I mean, in the digital age... you can almost do anything. I could play a 12-year-old girl at this point - in the digital age!

But approaching someone like John Dillinger, as opposed to Jack Sparrow, is it as in-depth?

It is, it's even potentially more so, because of the amount of responsibility you have, to that person who actually did exist. There's some sense of responsibility to their legacy. With John Dillinger, there's an enormous amount of information on the guy - we know where he was at 12:02, when the banks were robbed. But there's a great gap with regard to who he was. There's footage of him, there's endless photographs of him - but there's no audio. There's just an attitude. So, that was the dig - how do I find this man, how do I find the way he speaks. And what made the connection for me was that John Dillinger was born in Indiana, and raised in Mooresville, Indiana, which was 2 hours from where I was born and raised. It was at that point that I thought - ah, I hear his voice now, now I know him, I know what he sounds like, because it's not all that different. He was my grandfather, who drove a bus in the day, and ran moonshine at night. He was my step-father, who did time at Statesville Penitentiary. I knew his voice then.

Looking at you in this film, you don't seem to have changed much over the years. Do you have any particular skin-care regime?

[Laughs] Clean living. Oh yeah, most definitely. I say if you could avoid wine, I'd do it. And liquor, definitely. Avoid liquor. Most definitely don't smoke - anything. And stay in your room. And watch a bit of reality television, that's how I do it.

Looking at the extraordinary range of characters that you've played so far. Which has been the closest to you personally, and which has been the furthest away?

Well, the furthest away - oh boy, probably a couple of them. But, furthest away... might be Willy Wonka [laughs]. Let's hope that's the furthest! Closest to me, this would be horrifically revealing, wouldn't it? There's probably three, Edward Scissorhands, John Wilmot from The Libertine, and maybe Dillinger.

There's a great attention to detail in the film, in terms of shooting in real locations. How does that affect your performance, to know you're in a location where Dillinger himself was?

That was one of the amazing things that Michael Mann provided us with, that level of authenticity, to be able to break through the exact doors that John Dillinger broke though. As opposed to shooting on some soundstage because it was cheaper or handier to the studio. Michael was a real stickler for that thing, and I will thank him forever for that. To be able to go and fire my Thompson out of the very window John Dillinger fired his Thompson out of during the gun battle at Little Bohemia. You can't put a price on that thing. To be able to walk in the same footsteps as he took, to walk outside the Biograph theatre, and land exactly to the tiny millimetre where John Dillinger's head fell, in the alley near the Biograph was magical. I mean, you almost feel him arriving. Not to be moony or spooky, but there were moments when I felt his presence, moments when I felt a certain amount of approval from the guy. When you're going to that umpteenth detail, something's going on.

How did you find working with Christian [Bale]? Are your acting styles quite different?

I don't know if our acting styles are that different...

Christian tends to stay in character, and kept up the Southern accent between takes...

Oh, yeah, that kind of thing. Yeah, well I don't do that. But, if you have to do that, that's ok. I enjoyed our - basically - one scene together, besides when he and his cronies croaked me outside the Biograph [laughs]. Yeah, it was the scene in the jail cell, and I enjoyed it very much, it was like, how'd you describe it, like a great sparring match. Two guys in there with a similar respect for one another, trying to present different angles to each other. Obviously he's a very gifted actor, and very talented. When we saw each other, which wasn't very much, we talked about our kids, just talked about being dads. And that's where we really connected.

Could you tell us about Michael Mann - how was his style of directing?

I think, ultimately, Michael's style and my approach did complement each other. There are moments where, when you're building something, there will be things discarded - things will get broken along the way. So it wasn't right off the bat the easiest, but in the long run, what we were able to figure out together, was that, he presents something, he'd present something - we'd find a happy middle, and we'd get there. And we always got there. I have a tremendous amount of respect for Michael, as a human being but also as a filmmaker - he's not joking, you know. He truly means it.

Then it was my turn to ask a question. The last one of Johnny's press conference. Nervously I asked:

How difficult was it to let go of Dillinger once filming finished? And which character over your career has it been hardest to say goodbye to?

There's been a few. The funny thing is, you really don't say goodbye. There's a little chest of drawers in here [points at chest], where you can always access these guys. I'm not sure if that's healthy, but they're there. Saying goodbye to Dillinger was tough, because it was like saying goodbye to a relative. The most difficult to say goodbye to? Well, Scissorhands was rough. The safety of allowing yourself to be that honest, to be that pure, to be that exposed. That was hard to say goodbye to. Wilmot, Lord Rochester, on The Libertine, was incredibly tough, because I felt like it was a very intense 40-something days where I had the opportunity to be that guy. And I felt a deep sense of responsibility, so it was like a marathon. And then, in the end, it was like the light goes out and it's black.

Yesterday I was at the Public Enemies press conference in London. It was fantastic. It's not everyday you get a chance to listen to Michael Mann, Marion Cotillard and Johnny Depp talk about their films. I was also lucky enough to ask a question of both Marion and Johnny. Who would have thought it!

Yesterday I was at the Public Enemies press conference in London. It was fantastic. It's not everyday you get a chance to listen to Michael Mann, Marion Cotillard and Johnny Depp talk about their films. I was also lucky enough to ask a question of both Marion and Johnny. Who would have thought it!

Why did you say yes to Public Enemies?

Because I’m a great fan of Michael Mann and when he asked me to star I couldn’t believe it and I was very happy. I met him and read this beautiful script.

How was it doing the American accent and how did you prepare for that?

It was a technical issue and it was very hard. When I started I thought it was not possible at all, but I really tried to do my best. Fortunately Billie was half French, although she’s not supposed to have French accent.

It’s very technical. You really have to work and work. Practice and using your whole face, jaw, tongue, body in a total different way. It was very interesting. There were hours and hour in front of a mirror with my vocal coach because you don’t think how you speak.

There were so many men in this film. How did you feel being on set in one of the few female roles? Did you feel excluded?

No, absolutely not. Michael Mann has a great respect for women. He’s surrounded by women in his life and I think that is why the women in his movies are very strong. They really have strong personalities and they have a very special place in all his movies so I felt really welcome.

Michael asked you to meet some gangster’s wives and girlfriends. How was that?

They were actually convicts wives some of them were not with gangsters. They were all so generous to share their stories, the very painful experiences they had. We spent a few hours together and it was very emotional because they were very emotional going through the full story of their life.

More than their stories and they were important, but what they felt when they told me their stories. They went back through all those feelings, fear and extreme pain because you don’t know what’s going to happen when you are alone. Some of them had kids

*at this point Marion was distracted by one of the Dictaphones in front of her causing her to laugh *

I could see and feel their pain and fears because you don’t know what’s going to happen the next day. It helped me a lot. You gather some emotions and feeling. It creates your character.

You said you didn’t know anything about Dillinger as all so you must have done a lot of research to find out about him. He’s an American folk hero. Is he known in France at all?

I’m not very sure. I think that my generation doesn’t know Dillinger and yeah I didn’t know anything about him. I didn’t even know his name. The first thing I read about him was the script and the book, Public Enemies. I didn’t do a lot of research about him. My research was more about the period, the American history, and the Indian history because Billie Frechette is half [Menominee] Indian. I really wanted to know about American culture and Indian culture. I knew about the era I learnt at school about the crisis in the Thirties, but I didn’t know that much about American history. What I read about Dillinger was just the script and the book. I watched a lot of pictures of him, but my research was on the Thirties and the American culture.

I never talked about Dillinger with anyone. He may be well known with French people.

Was the experience of working with Michael Mann more than you anticipated?

When I met him, right away, when I came in his office I felt that there was a connection between the two of us. I don’t know how to explain it. I really love him as a person and a director. I wanted to be perfect for him. I wanted to give the best of my best. I don’t know if I did. He was inspirational.

Then it was my turn. I was the gentleman in the third row!

What was it like filming the interrogation scene? How much preparation did you have to do?

The difficulty of the scene was that when you have a very emotional violent scene to do you think of the technique and I had to keep the mid-western accent. It was very difficult, as I had to let it go but at the same time not think about.

I love extreme scenes. I would say that after this kind of scene I feel empty but also fulfilled. I think it may feel like when you do sports and you have a competition like the 100m. After that you feel tired and empty but fulfilled because you did something that was intense. I really love it. It’s not difficult but it is technical.

How deeply did Christian Bale and everyone stay in character? He apparantly kept his accent on between scenes

I didn’t work with him too closely. When we were filming everything was in the Thirties. I think there is something that stays with you while you film. For example if you have an accent you keep it between the scenes, as it is hard to get there. Sometimes it is better to stay there even when you are not shooting, because if you totally get out of it to come back is the same journey. Before I did La Vie en Rose I thought it was dangerous to stay in character and more than that I thought it was kind of ridiculous. I had a judgement because I didn’t know that it’s really hard to go back there. After that my opinion, it was not even an opinion it was a stupid judgement because I didn’t know what I was talking about. Now I know I didn’t force myself to stay in character. It was easy. I couldn’t stop between takes because it was so much work to get there. I really do understand this now.

Director: Michael Mann

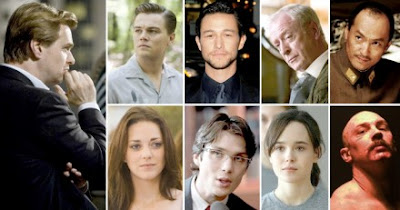

Director: Michael Mann NolanFans.com found the above picture of Leonardo DiCaprio, Christopher Nolan and Ken Watanabe in a Japanese magazine. I'm not sure if Leonardo and Ken are in costume or if it is just for the photo.

NolanFans.com found the above picture of Leonardo DiCaprio, Christopher Nolan and Ken Watanabe in a Japanese magazine. I'm not sure if Leonardo and Ken are in costume or if it is just for the photo.The photo containing the Inception director, and two of its stars, was taken on June 15th in Tokyo, Japan (one of the reported filming locations of Inception). According to reports, filming is already underway in that country, which is only one of six reported countries the film is scheduled to shoot in.As well as Japan Inception will also film in Los Angeles, London, Paris, Morocco, Tangiers and Canada (as mentioned here). It has been described as “a contemporary sci-fi actioner set within the architecture of the mind” and as as well as Leo and Watanabe the cast includes Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Ellen Page, Marion Cotillard, Michael Caine, Tom Hardy and Cillian Murphy.

A new online game created by Universal Pictures International to promote upcoming movie Public Enemies is using Facebook Connect and Twitter to create a new form of social gaming experience.

A new online game created by Universal Pictures International to promote upcoming movie Public Enemies is using Facebook Connect and Twitter to create a new form of social gaming experience. A Sun source confirmed that Leonardo DiCaprio will be heading to Alberta, Canada this November to shoot scenes for the new Christopher Nolan film, Inception.

A Sun source confirmed that Leonardo DiCaprio will be heading to Alberta, Canada this November to shoot scenes for the new Christopher Nolan film, Inception. Source: Calgary Sun

Source: Calgary Sun

Discuss in the forum or leave a comment below.

HOME

Here is a trailer and some photos for Nine. It is a musical in the style of Chicago which I thought was terribel, but that's just me.

Here is a trailer and some photos for Nine. It is a musical in the style of Chicago which I thought was terribel, but that's just me. The musical tells the story of world famous film director Guido Contini (Daniel Day-Lewis) as he prepares his latest picture and balances the numerous women in his life including his wife (Marion Cotillard), a producer, a mistress (Penelope Cruz), a film star muse (Nicole Kidman), an American fashion journalist (Kate Hudson), the whore from his youth (Fergie), his confidant and costume designer (Judi Dench), and his deceased mother (Sophia Loren).

The musical tells the story of world famous film director Guido Contini (Daniel Day-Lewis) as he prepares his latest picture and balances the numerous women in his life including his wife (Marion Cotillard), a producer, a mistress (Penelope Cruz), a film star muse (Nicole Kidman), an American fashion journalist (Kate Hudson), the whore from his youth (Fergie), his confidant and costume designer (Judi Dench), and his deceased mother (Sophia Loren). Nine is directed by Rob Marshall (Chicago, Memoirs of a Geisha). The screenplay was adapted by filmmaker Anthony Minghella and Michael Tolkin. The film is based on Federico Fellini's masterpiece 8½.

Nine is directed by Rob Marshall (Chicago, Memoirs of a Geisha). The screenplay was adapted by filmmaker Anthony Minghella and Michael Tolkin. The film is based on Federico Fellini's masterpiece 8½.

So Fergie is in this, will.i.am was in Wolverine and Taboo was in Street Fighter. What will the last Black Eyed Pea, apl.de.ap, star in?

So Fergie is in this, will.i.am was in Wolverine and Taboo was in Street Fighter. What will the last Black Eyed Pea, apl.de.ap, star in?

Character posters for Michael Mann's new film. The Johnny Depp one above doesn't look quite like Depp for some reason. In fact all three posters seem a little off. Still looking forward to seeing the film though.

Character posters for Michael Mann's new film. The Johnny Depp one above doesn't look quite like Depp for some reason. In fact all three posters seem a little off. Still looking forward to seeing the film though.